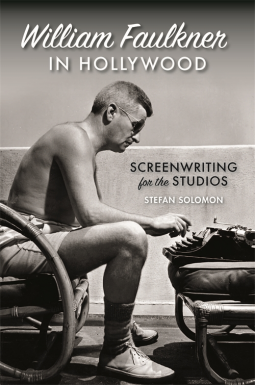

William Faulkner in Hollywood

Screenwriting for the Studios

by Stefan Solomon

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Aug 01 2017 | Archive Date Jul 31 2017

Description

During more than two decades (1932–1954), William Faulkner worked on approximately fifty screenplays for studios, including MGM, 20th Century–Fox, and Warner Bros., and was credited on such classic films as The Big Sleep and To Have and Have Not. The scripts that Faulkner wrote for film—and, later on, television—constitute an extensive and, until now, thoroughly underexplored archival source. Stefan Solomon not only analyzes the majority of these scripts but compares them to the novels and short stories Faulkner was writing at the same time. Solomon’s aim is to reconcile two aspects of a career that were not as distinct as they first might seem: Faulkner as a screenwriter and Faulkner as a high modernist, Nobel Prize–winning author.

Faulkner’s Hollywood sojourns took place during a period roughly bounded by the publication of Light in August (1932) and A Fable (1954) and that also saw the publication of Absalom, Absalom!; Go Down, Moses; and Intruder in the Dust. As Solomon shows Faulkner attuning himself to the idiosyncrasies of the screenwriting process (a craft he never favored or admired), he offers insights into Faulkner’s compositional practice, thematic preoccupations, and understanding of both classic cinema and the emerging medium of television. In the midst of this complex exchange of media and genres, much of Faulkner’s fiction of the 1930s and 1940s was directly influenced by his protracted engagement with the film industry.

Solomon helps us to see a corpus integrating two vastly different modes of writing and a restless author, sensitive to the different demands of each. Faulkner was never simply the southern novelist or the West Coast “hack writer” but always both at once. Solomon’s study shows that Faulkner’s screenplays are crucial in any consideration of his far more esteemed fiction—and that the two forms of writing are more porous and intertwined than the author himself would have us believe. Here is a major American writer seen in a remarkably new way.

A Note From the Publisher

Stefan Solomon is a postdoctoral researcher in lm at the University of Reading. He is coeditor, with Julian Murphet, of William Faulkner in the Media Ecology. Part of the South on Screen series.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780820351131 |

| PRICE | $49.95 (USD) |

| PAGES | 320 |

Links

Average rating from 5 members

Featured Reviews

Steven M, Reviewer

Steven M, Reviewer

Stefan Solomon takes us on a wonderfully researched journey through approx 2 decades of the accomplished writers life whilst comparing his body of work. From his film and tv scripts which he didn't love doing, to his totally different work on his Nobel Prize winning novels. Analysis is also given on the differences of his scripts and short stories written at the same time. An enjoyable new book that shows a previously unseen side to a great American storyteller.

Kendahl C, Reviewer

Kendahl C, Reviewer

William Faulkner was different from literary greats like F. Scott Fitzgerald and John Steinbeck who came to Hollywood chasing a big paycheck and then struggled to adapt. The novelist not only adjusted well to studio life, but thrived. In a new book, Stefan Solomon examines Faulkner's Hollywood experience and how it colored his creative output.

While Faulkner's time writing screenplays took him away from more personally satisfying literary pursuits, it also gave him the financial resources to continue that work, in addition to providing inspiration for its development. His practicality on that front, and his adaptability and ability to understand the demands of cinema worked enormously to his benefit. He was able to write in the style of different studios, finding success at RKO, MGM and Warner Bros, collaborating on fixing and conceiving projects, looking upon the whole enterprise as a job, though it was not without its artistic inspirations.

In fact, the inspiration ran two ways when it came to Faulkner's writing during his Hollywood years. The rich world of his literature colored his screenplays and sometimes that day work inspired his novel writing in the early morning hours, before he headed to the studio. Hollywood was never the dream. Faulkner always preferred his Mississippi home, but the writer embraced the opportunities movie money offered while reaping those creative benefits.

Faulkner was unusual among novelists in his grasp of the visual and aural language of movie writing. He was adept at integrating stage direction and sound into his scripts, creating a world to accompany his dialogue. On the other hand, the power of dialogue impressed itself upon the novelist, and he would begin to insert more of it in his literary works.

As a script fixer, Faulkner had a knack for adding dramatic tension, pumping life into literary sources so that they could live on the screen. He understood the needs of the cinematic form as well as he did their differences from literature. For example, director Jean Renoir felt Faulkner's small, but significant contributions to the script of The Southerner (1945) helped to translate its literary source to the screen. When the writer created a scene about competition over catching a desired fish, it both added dramatic tension and resolved an important plot thread.

The book examines both Faulkner's credited and uncredited work, demonstrating how, as with the Renoir film, the writer could significantly affect a movie with as little as a single scene or a few lines of dialogue. These efforts include work on films as diverse as Gunga Din (1939), Mildred Pierce (1945), The Big Sleep (1946) and Drums Along the Mohawk (1939). It is interesting to note that while Faulkner was more often contributor than lead, he tended to work on films that would become classics.

This is a highly accessible academic work, appropriate for the casual reader. It goes deep into the details, and reader interest will depend on whether or not that kind of analysis is appealing. The focus is on craft, with very little personal detail. Faulkner's methods and the way he navigated Hollywood take center stage.

Perhaps William Faulkner belonged in Mississippi, writing novels and eating watermelon on his back porch, but he made the most of his time in Hollywood. William Faulkner in Hollywood captures the unusual combination of vision, industry and practicality that made that so.