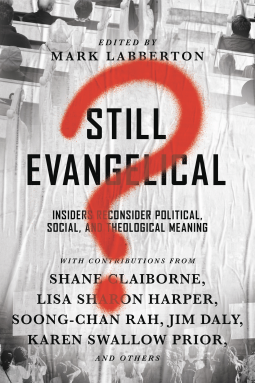

Still Evangelical?

Insiders Reconsider Political, Social, and Theological Meaning

by Edited by Mark Labberton

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Jan 23 2018 | Archive Date Feb 14 2018

InterVarsity Press | IVP

Description

Evangelicalism in America has cracked, split on the shoals of the 2016 presidential election and its aftermath, leaving many wondering if they want to be in or out of the evangelical tribe. The contentiousness brought to the fore surrounds what it means to affirm and demonstrate evangelical Christian faith amidst the messy and polarized realities gripping our country and world. Who or what is defining the evangelical social and political vision? Is it the gospel or is it culture? For a movement that has been about the primacy of Christian faith, this is a crisis.

This collection of essays was gathered by Mark Labberton, president of Fuller Theological Seminary, who provides an introduction to the volume. What follows is a diverse and provocative set of perspectives and reflections from evangelical insiders who wrestle with their responses to the question of what it means to be evangelical in light of their convictions.

Contributors include:

- Shane Claiborne, Red Letter Christians

- Jim Daly, Focus on the Family

- Mark Galli, Christianity Today

- Lisa Sharon Harper, FreedomRoad.us

- Tom Lin, InterVarsity Christian Fellowship

- Karen Swallow Prior, Liberty University

- Soong-Chan Rah, North Park University

- Robert Chao Romero, UCLA

- Sandra Maria Van Opstal, Grace and Peace Church

- Allen Yeh, Biola University

- Mark Young, Denver Seminary

Referring to oneself as evangelical cannot be merely a congratulatory self-description. It must instead be a commitment and aspiration guided by the grace and mercy of Jesus Christ. What now are Christ's followers called to do in response to this identity crisis?

Advance Praise

"Evangelical should mean Bible believing, gospel preaching, justice seeking, and Spirit filled. Instead it has become known more by its politics than by its commitment to the Word of God. This book puts the current evangelical identity crisis within a much needed historical perspective and provides a way forward to help us recover the good news of Jesus that our world desperately needs to hear."

- Aaron Graham, lead pastor, The District Church, Washington, DC

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780830845378 |

| PRICE | $25.99 (USD) |

Links

Average rating from 8 members

Featured Reviews

A common thread of Still Evangelical? appears to be a protest that American, politically orientated, pale,stale males are not the only Evangelicals on the planet.

I particularly enjoyed Shane Claibourne’s essay, or should it be called a call to action. Shane writes directly, with a challenge to re-orientate ourselves from mere belief to living as Jesus calls us to. My favourite quote – “Perhaps there is a new evangelicalism that rises from the compost of the old.”

Lisa Sharon Harper’s perspective was a clear sighted call to re-orientate our understanding of who belongs in the Evangelical family. She calls for a differentiating of compassion and justice, and offers new thinking on shame.

Tom Lin asks for a more global perspective of the movement. Tom’s thinking about collaborations which cross tribal, organizational and historical boundaries opens a window on a fresh path for the future of evangelicalism.

I also enjoyed Allen Yeh’s discussion about faith and works, as he pushes back against some Evangelical’s definition of Christianity as intellectual assent. He joined Shane Claibourne (and Pope Francis) in calling for a pro-life stance from the womb to the tomb. And Mark Galli’s comments about fear on both sides of the evangelical divide were astute and thought provoking.

One tiny whinge - perhaps there were one or two too many descriptions of Bebbington’s Quadrilateral as a definition of evangelicalism. One in the introduction would have sufficed. But overall, a very interesting collection of essays for an interesting time in Evangelical history.

Justin C, Media/Journalist

Justin C, Media/Journalist

The question making the rounds – “Do you still consider yourself an evangelical?” – has theological, political, and cultural ramifications. This book collects essays from a dozen writers (if you count editor Mark Labberton's valuable introduction) to address that question. The list of authors includes plenty of names you should know (and probably more I should know if only I knew I should know them) from across the political spectrum, and each one makes a worthy contribution.

Whether each thinker defines herself as still (or ever) an evangelical is not so much a priority as is the question of what the term “evangelical” itself means. Several essays reference the Bebbington quadrilateral (biblicism, crucicentrism, conversionism, activism) in their work, but the problem seems to lie in the shift in usage since Bebbington and even Mark Noll's landmark writings. The term now has specific political implications. “Evangelical” now, in general usage, tends to define not only what you believe and how you respond to that belief, but how you vote.

The writers here try to suss out that matter in various ways, often not explicitly claiming or not the label for themselves, but sorting out the meaning in the process. Shane Claiborne, for example, wants to shift the thinking toward the Red Letter Christianity that he identifies with. Lisa Sharon Harper traces the problems with the term to somewhere earlier in its history than, say, the rise of the Moral Majority.

Mark Young does address his own status, stating his continuing connection to evangelicalism to be grounded in the gospel of Jesus Christ. He sees the deep cracks in the tradition's public outworking and seeks to find a way forward not through partisanship but through missional ecclesiology. Karen Swallow Prior takes a different path, finding her connection to evangelicalism not in the current political climate but in historical and biographical reasons, acknowledging that “Robust Christianity is not for the faint of heart – or the faint of mind.” The challenges are part of the deal, and are no reason to abandon deep traditions.

Each essay in the book has something to contribute. It'd be nice to see these writers in conversation with each other, but that's not the point of the text (though maybe a panel discussion with four or five of them would really push these ideas). Still Evangelical? is a smart and timely entry into a discussion that's likely to reverberate for a while.

Adam S, Reviewer

Adam S, Reviewer

Takeaway: The meaning of the word evangelical is complicated. The groups it refers to still are present, even if there is reform necessary.

I am ambivalent about the word Evangelical. Theologically I am a bit on the edge of the term, depending on how it is defined. Sociologically, I am a bit further away from the term if it is used to describe a political grouping (Religious politically conservative Whites.) Historically, I grew up in an Evangelical section of a mainline denomination while participating with solidly evangelical youth groups of friends before heading to Wheaton College before going to seminary at a decidedly non-Evangelical institution (University of Chicago Divinity School). I currently am a member at an evangelical non-denominational mega-church. So I have some historical background, theological bias, but politically I am a Democrat and incredibly frustrated with the political definition of Evangelical, especially around racial issues.

I initially wasn’t going to read Still Evangelical. But I appreciate Karen Swallow Prior even if I disagree with her at times. In spite of my reluctance I picked up a review copy and expected to be mostly frustrated. It is not that I wasn’t occasionally frustrated. But I also really appreciated the choice of authors and the directness of the discussion about the weaknesses of the Evangelical movement, especially locally within the United States. It is a rare collaborative book like this that is actually well put together and balanced. Still Evangelical really is balanced. It has very pointed and direct criticism, but also a lot of love for and hope for the church as a whole and the Evangelical church in particular.

The subtitle is ‘Insiders Reconsider Political, Social, and Theological Meaning’ (of the word Evangelical.) And these are insiders. Not every name is a household name. But all of them have paid their dues and are solid Evangelicals by history, by institution, and by love of the church.

It is a rare book published in the Evangelical world that is has as many chapters by minorities and women as by White males. The diversity of the authors matters to how positively I feel about the book. After the introductory chapter by Mark Labberton, President of Fuller Seminary and the editor of the book, only one of the first five chapters was by a white male, although three of the five last chapters are by white men. (Two additional names are listed in the Amazon description that are not in the pre-release edition that I have.)

Lisa Sharon Harper focused on the weaknesses of the cultural understanding of Evangelicalism, particularly around the idea of justice, especially around race.

Karen Swallow Prior balanced her own understanding of her place in Evangelicalism as someone that grew up in and was formed by Evangelicalism with the historic understanding of the term, especially from its British history and the way that British Evangelicals were expanding the role of the church into social justice.

Mark Young suggests that the way forward is to recapture what it means to be Evangelical by focusing on its theological identity and mission rather than its sociological or political background.

Soong-Chan Rah pointed to the need to pay attention to the Evangelicalism that is outside of the US. He believes that the root of the problem of evangelical identity is American Exceptionalism that views Evangelicalism as primarily American and not seeing American Evangelicals as part of a worldwide community.

Allen Yeh had a wide ranging chapter (and the best chapter) about the need for Evangelicalism to balance its current bias toward a theological orthodoxy with orthopraxy that is rooted in world-wide community. The western Evangelical world needs to develop more focus on right action while retaining orthodoxy and the majority world needs to be given more space to develop theologically within their cultures. Yeh resists the idea that orthodoxy can really exist without orthopraxy. There is far more to this chapter, but the main focus is that orthopraxy along with orthodoxy need to come together so that there can be real unity within the church as a whole, but also within the Evangelical community worldwide.

Mark Galli has a mostly pessimistic take on Evangelicalism. As the editor for the periodical most closely associated with Evangelicalism, Christianity Today, he is aware of the problems and strengths. He points primarily to the disconnect between the elite and non-elite Evangelicals. (Karen Swallow Prior in a similar vein on Twitter Saturday night was positing that outside of pundits and professionals, she did not think most Evangelicals used the word to describe themselves.)

One interesting comparison that he made was to Puritanism. Evangelicalism today is defined quite differently by those outside of the movement than it is by those inside the movement.

Where I think Galli is wrong is that he wants to give the benefit of the doubt to Trump voters and others as a sort of economic or cultural determinism. The polling and research seems to suggest that racial vulnerability, not economic or cultural insecurity was a primary driver of Trump voters. If this line of thought is right, then the understanding of economic and cultural differences between elite and non-elite or left and right parts of evangelicalism or the coasts and the flyover parts of the country may be results of differences of other attitudes instead of the drivers of those attitudes. (But Galli would probably suggest that I am proof of his assertions.)

There is a lot that Galli says that I think is right. The problem is that I think of the of the assumptions that give rise to what he says that is wrong. But this book, if anything, needs more contrary ideas.

Shane Claiborne’s chapter is the shortest and weakest of the book. He talks about being a Red Letter Christian and how actually paying attention to Jesus’ words are important. It adds very little to the overall conversation.

Jim Daly’s contribution is short but helpful. Daly is the current leader of Focus on the Family. Daly points out how the second generation of leadership of many personality driven organizations is more focused on organizational leadership and less on charismatic leadership. He also points out the strength of the democratization of media. The rise of self publishing, blogging and podcasting means that there are many outside of the traditional Evangelical leadership that are speaking. Healthy leadership is a leadership that listens, not just to God (although that is important) but also to those around them, especially those that have different perspectives.

Tom Lin ends with a hopeful essay revisiting the importance of seeing Global Evangelicalism as the center of our discussion about Evangelicalism within the US. As the head of Intervarsity, a trustee at Fuller Seminary, and a trustee of a large Evangelical Foundation he sees the shift in Evangelicalism away from some of the old and toward some of the new. I think he is right to be hopeful when he focuses us on global Evangelicalism.

His hopefulness is in part based on his work with mostly young people. And that is where my hope is mostly based as well. But I am not sure that you can point to the global definition of a word as taking priority over the local. I think it is a weakness of this whole project.

The word Evangelical refers to a global, historical and theological movement. One that is growing world wide. One that has theological and ecclesiastical strength. But also one that has some significant problems locally within the US.

As one side note: I have always understood Bebbington’s Quadrangle, which is referenced a number of times in this book as Biblicism, Activism, Personal relationship with Christ and the need to share that personal relationship (evangelism) and Christologically focused. It wasn’t until I read this last chapter that I realized that the official term isn’t Christological, but Cruciform. I think there is a different between a focus on the work of the Cross and on the person of Jesus. My personal theological biases are uncomfortable with the way that some Evangelicals become bibliocentric in a way that can sometimes appear to be almost idolatrous. I am okay with the basic idea of the activism and Evangelism, although the individualistic part of the Evangelism does give me pause at times. But I am much more focused on Christological understanding than a Cruciform focus.

I think the cross is historical and important and the death and resurrection are both real and physical. But I think the incarnation and life of Jesus, as well as the reality of the resurrection are just as important as the actual death. Christ wasn’t only here to die. He was also here to live.

Still Evangelical is worth reading if you are interested in the direction of the group that is currently called Evangelical. The movement isn’t going away regardless of the term that is used to identify it. I think the discussion about the term is important to the extent that words matter. And while not everyone is particularly interested in word choice, it is not merely semantics. One problem is that while I think that this is a balanced take, paying attention to the critiques slightly more so that they are understood, the problem with the cultural/political understanding of Evangelical is that those that are only cultural/political will have no interest in the critiques.

I've often wondered what it actually means to be evangelical. It wasn't a term I was even familiar with until the last few years. This series of essays by influential evangelicals gives you a history of the term, how it has impacted history, and what its future might look like. I appreciated all of the perspectives in one place, and learned so much. One of my favorite parts of the book was overall, it offered possible restructuring ideas, but remained positive towards this group of Christians.

Lisa B, Reviewer

Lisa B, Reviewer

“We seem to have forgotten who we are and why we are who we are.”

– Mark Young

If you once considered yourself an evangelical, do you now? It’s a question many wrestle with. It's also the question asked over and again in this book. It is answered by ten different voices from the Christian community, including these:

Shane Claiborne, Red Letter Christians

Jim Daly, Focus on the Family

Mark Galli, Christianity Today

Lisa Sharon Harper, FreedomRoad.us

Tom Lin, InterVarsity Christian Fellowship

Karen Swallow Prior, Liberty University

Soong-Chan Rah, North Park University

Allen Yeh, Biola University

Mark Young, Denver Seminary

Nobody gives a perfect answer. There are none. In the book, some ask more questions. Some propose suggestions. Some agree; some disagree. But all the voices are interesting to hear and their opinions are worth listening to. Here are a few excerpts from various speakers.

~ * ~

"The efforts spent on defending our turf in the culture wars could be better served in loving our neighbor as ourselves."

~ * ~

"Christians in America in general have an image problem. When the Barna Group polled the country and asked young non-Christians what their perceptions of Christians were, the top responses were (1) anti-gay, (2) judgmental, and (3) hypocritical. . . .The very thing that Jesus said the world would know we are Christians by—love—didn’t even register on the chart."

~ * ~

"I realize Christians don’t always have the best reputation in the world, but I see that as a challenge to sing a better harmony rather than give up on the choir."

~ * ~

"Every human being is made in the image of God, and any time a life is lost, we lose a little glimpse of God in the world."

~ * ~

"I believe we should have two questions on the tip of our tongue as we engage with those around us: 1. Help me understand what you believe. 2. What brought you to those conclusions?"

My thanks to NetGalley for the review copy of this book.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Peter H. Reynolds with Paul A. Reynolds

Children's Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality