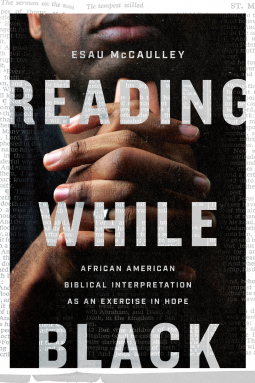

Reading While Black

African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope

by Esau McCaulley

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Sep 01 2020 | Archive Date Oct 01 2020

InterVarsity Press | IVP Academic

Talking about this book? Use #ReadingWhileBlack #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

Outreach Resources of the Year, Christianity Today Book Award, The Gospel Coalition Book Award

Biblical Interpretation from the Black Church Tradition

Growing up in the American South, Esau McCaulley knew firsthand the ongoing struggle between despair and hope that marks the lives of some in the African American context. A key element in the fight for hope, he discovered, has long been the practice of Bible reading and interpretation that comes out of traditional Black churches. This ecclesial tradition is often disregarded or viewed with suspicion by much of the wider church and academy, but it has something vital to say.

Reading While Black is a personal and scholarly testament to the power and hope of Black biblical interpretation. At a time in which some within the African American community are questioning the place of the Christian faith in the struggle for justice, New Testament scholar McCaulley argues that reading Scripture from the perspective of Black church tradition is invaluable for connecting with a rich faith history and addressing the urgent issues of our times. In Reading While Black, Esau McCaulley:

- Advocates for a model of interpretation that involves an ongoing conversation between the collective Black experience and the Bible,

- Gives pride of place to the particular questions coming out of Black communities,

- Gives the Bible space to respond by affirming, challenging, and at times, reshaping Black concerns, and

- Demonstrates this model with studies on how Scripture speaks to topics often overlooked by white interpreters, such as ethnicity, political protest, policing, and slavery.

Ultimately McCaulley calls the church to a dynamic theological engagement with Scripture, in which Christians of diverse backgrounds dialogue with their own social location as well as the cultures of others. Reading While Black moves the conversation forward.

Advance Praise

"Although the African American Christian experience is not monolithic, we have generally sought to understand the Bible and live according to its teachings. Along the way, many of us have rejected white supremacist readings of the Bible while clinging to the God of the Bible. In Reading While Black, McCaulley does careful exegetical and historical analysis, explaining and illustrating how interpretations of Scripture by Black people can bolster faith in a liberating God. McCaulley gives us more than a theoretical methodology; he demonstrates how we can approach and apply texts—even ones that were previously used against us—without jettisoning our faith or succumbing to oppressive readings. Reading While Black is a welcome addition to the study of African American hermeneutics."

-Dennis R. Edwards, associate professor of New Testament at North Park University

"I'm extremely grateful to have a voice in my time to speak with nuance, grace, and cultural awareness. Esau has given us a healthy marriage for understanding theology and blackness. This is a must-read!"

-Lecrae, hip hop recording artist

"It is enlightening, moving, and galvanizing to overhear these notes of appreciation and reciprocated encouragement from a son of the Black church to the Black ecclesial interpreters who nurtured and continue to nourish him. From here on out, this book will be required reading in any course on biblical hermeneutics that I teach."

-Wesley Hill, associate professor of biblical studies, Trinity School for Ministry

"When I was a student, I was explicitly and implicitly trained to focus exclusively on the ancient context of Scripture and read 'objectively.' Bible study could easily become a disembodied experience. McCaulley makes a compelling case, in this engagement with African American biblical interpretation, that not only is the reader's culture and experience not a hindrance to interpretation per se but can enrich it greatly. Reading While Black is a unique and successful blend of biblical hermeneutics, autobiography, black history and spirituality, incisive cultural commentary on race matters in America, and insightful exegesis of select New Testament texts."

-Nijay K. Gupta, professor of New Testament at Northern Seminary

"Throughout history the church, as it strives to be faithful in particular times and places, has had to bring the core cultural concerns of their neighbors to Scripture for answers. This is the work of loving our neighbors well. What does God have to say about the animating issues of our lives and communities? In Reading While Black, Rev. Dr. Esau McCaulley puts in bold relief before us the historic and present concerns of the African American community. Does God have a word for us about policing? Is there any guidance from on high about Black identity, justice, righteous anger, slavery, and oppression? With sound exegetical method, deep cultural insight, and skillful application he brings us into the heart of God on these issues. Know, however, that this is not just a book for Black people. Far from it. Anyone who desires to engage these questions with gospel hope should take up and read."

-Irwyn L. Ince Jr., director of the GraceDC Institute for Cross-Cultural Mission and author of The Beautiful Community

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780830854868 |

| PRICE | $23.99 (USD) |

| PAGES | 200 |

Average rating from 33 members

Featured Reviews

Reading While Black takes a look at African American interpretations of the bible and how they differ from conventional interpretations from white churches in America. I would clarify that these interpretations are not so different that they diverge from biblical canon. Instead, it focuses on the idea that Christianity is about freeing the oppressed and unity for all races and ethnic backgrounds. There are many examples of this in the bible (ie. Moses leading the slaves to freedom, and the unification of Jews and Gentiles). He also points out that one of the places Christianity originated from is North Africa.

With that in mind, I really enjoyed reading about interpreting the bible through a different perspective. As an Asian American who grew up in white evangelical churches, it can be really isolating when biblical norms seems to tie into white culture. Over time, I've been trying to expand my knowledge on how the bible is interpreted by different groups of people. Reading about Black Christian culture and its biblical interpretations has been really enlightening and incredibly important. I find that it helps us develop a more holistic view of the bible that's not homogenous to an individual culture or perspective. Reading While Black is an important book that gives us a window into the Black Christian identity, and shows us that God's redemptive grace is for the oppressed, and standing against injustice is in fact a biblical thing to do. I encourage people from a traditional western Christian background to read this book in order to understand the bible from a different lens.

Erin L, Reviewer

Erin L, Reviewer

"God's vision for his people is not for the elimination of ethnicity to form a colorblind uniformity of sanctified blandness. Instead God sees the creation of a community of different cultures united by faith in his Son as a manifestation of the expansive nature of his grace. "

As a white woman who grew up in a white community in a white church, attended a preodominantly white college and currently works in a predominantly white industry, I have long thought the goal as far as racism goes, was to be "colorblind". And I succeeded at that. I also thought that the stories I'd seen on the news were exceptions, and not the rule, to how Blacks were treated in our nation. Recent events have spurred on conversations with people of color and have let me know that I have absolutely no idea what I'm talking about. So, I need to be educated. As this book relates to how Blacks see the scriptures, I felt like this was a good place to start, and indeed it was! This was an eye-opening tome as far as the differences we experience, in even how we interpret the scriptures (for example, the Exodus hits a lot closer to home for a person whose great-grandmother had been enslaved).

After the initial introduction to what the author terms "black ecclesial interpretation", each chapter speaks to a Black experience and how the scriptures relate. While I personally felt more attention was drawn to both politics and slavery (slavery, while an important topic, took up 20% of the narrative, and 150 years removed from the Emancipation Proclamation, I don't think should have consumed quite that much of the book) than should have, I anticipate that the intended readers of this book will find it more appropriate. As I simply don't care for politics at all (though I know that this is a pressing concern for Blacks), any conversation about that is too much almost to me. One thing that I struggled with in that chapter was how the author was comparing Paul's exhortation to pray for our leaders to our current leaders and seemed to imply that today's leaders were worse. However, at the time of that writing, Paul was under the authority of Nero. With the checks and balances we have in place in our country, I'm pretty sure that no matter how corrupt the politician, they would not be worse than Nero. But perhaps I interpreted what he was saying wrong. That was really the only content issue I took with the book. Chapter 5 was the strongest chapter for me, where the author discussed black identity and brought to light the many Africans in Scripture who go before us as part of the Biblical narrative. I loved that being brought to light. All in all, this gave me a lot to think about and gave me a brand new perspective on theology.

A couple of things I will note:

1. Mr. McCaulley is a highly educated theologian. As a person who generally reads fiction (and therefore deals only with common vernacular in books), it took me some time to get accustomed to the verbiage in this book. While I recognize and understand words like "eschatology", "exegetical" and "paradigmatic", they're not words I commonly use or see, so I often had to slow down and "translate" in my head what was being said. Readers who are accustomed to this type of language will have no issues though.

2. Because I read an e-copy of the Galley, there was a smattering of grammatical and spelling issues, as well as formatting issues. Because I assume these will be taken care of in final editing before the book is actually released, I'm not deducting any stars from my rating for it as I normally would have, but do want to note it in case they are not fully edited.

Special thanks to the publisher and NetGalley for an advanced copy of this book. I was under no obligation to write a review and the thoughts contained herein are my own.

Adam S, Reviewer

Adam S, Reviewer

Summary: Exploration of how reading in the diverse Black Church Tradition works in several practical examples.

About a year ago, I first heard of Esau McCaulley. I do not remember if I heard of his new appointment to Wheaton College New Testament faculty (my alma mater) or if I saw him at the Jude 3 Conference first. Regardless, I have paid close attention to him since. He has written many articles this past year for Christianity Today (including this month's cover article on policing adapted from this book), the New York Times (where is he is contributing opinion writer), Washington Post, and others. And he had an interview podcast with ten episodes so far. I am also about halfway through a free podcasted seminary class, The Bible in Color, which has some overlapping content with the book. My point of noting all of this is that once you have read this book, there is more to follow up with. And that I was not entering the book brand new.

Reading in Black is not trying to survey the entirety of Black biblical tradition of biblical interpretation, but to give an introduction to the fact that there is a diverse tradition of biblical interpretation that matters. The book opens to tracing, somewhat autobiographically, why the Black biblical tradition matters. And the book ends with a 'bonus track' on some of the development of the academic Black biblical tradition. And he notes that the three general streams of the black church "revolutionary/nationalistic, reformist/transformist, and conformist" tend to only include academic expressions of the first and the last. McCaulley is more in the middle and wants to encourage more work in that reformist/transformist stream. Part of that first chapter that I have seen myself, is how important it is to be historically conversant in the actual words of the Black church, not just what has been said about those words.

Between that opening and closing are five chapters that illustrate what it means to interpret the bible as a Black man in the Black church tradition. The chapter that was developed into the article at Christianity Today, is an exploration of the New Testament and the theology of policing. It centers around Romans 13, the passage that is frequently trotted out as a basis of supporting the political status quo, and shows why social context matters, but also how social context is not the only thing that matters when reading scripture. (That last bonus chapter explores the limits of social context in biblical interpretation more.) The Black church tradition has emphasized that the bible is not a string of proof texts, but an overall narrative that centers the liberating work of Christ throughout history. This means that interpreting Romans 13, apart from the reality that the subjects of authority are still made in the image of God, impacts how we see justice. Abstracting authority from the imago dei allows us to support dehumanizing tactics by removing the humanity of the subject of the authority from the ethical discussion.

I do not have time to get into each chapter, but the other illustrating chapters discuss, the political witness of the church, the pursuit of justice, Black identity, Black anger, and slavery. All of these subjects are worth reading, and the content is very accessible and treated in enough depth to get an introduction to the concept but, not so deeply to go over the head of most lay readers.

One of the messages that came through clearly in the book was that because of a lack of familiarity with the Black church tradition, that many institutions, which are predominately white Christian institutions, force students or staff or participants in the Black church tradition to be conversant in white Christian biblical interpretation, and then rely on those students or staff to learn more about their own Black church tradition on their own. One story McCaulley related was about speaking to a group of COGIC pastors who lamented that they could either send their seminary students to Evangelical seminaries which would teach them to ignore the historic practices and social integration of the Black church, or they could send them to more liberal mainline seminaries which would take more seriously the Black church social tradition, but teach them to discount the theology of the Black church. And further, internal Black church discussions of theology are often stripped of context by white listeners and used as a method of delegitimizing the Black church as a whole.

The point of this book seems to be to introduce the tradition of Black biblical interpretation to not only Black Christians but for all Christians. And it was an excellent introduction. The chapters are short, and I think it would make for a great small group discussion (there is a discussion guide at the back of the book.) And there is a strong hint at follow up book(s) that explore other areas and more of the historically Black church tradition. There is a significant discussion right now about what justice means in the church. And too much of that discussion is lacking in historical and theological context. Reading While Black is a helpful addition to that discussion and I encourage you to follow not only Esau McCaulley but many other Black church advocates (like Isaiah Robertson) that are rightly pointing out that the part of what is needed in a divided white evangelical church is a more robust understanding of what it means to be the church and the Black church tradition can help speak into that context.

I hadn't at all talked about the subtitle, "An Exercise in Hope". Hope is a significant Black church theme and one that I am a bit ambivalent about. Hope is about eschatology. And eschatology is important as Christians. At the same time, hope is sometimes used, especially by White Christians, as a way to deny the lived reality of Black and other minority Christians. There is a problem with only being hopeful in the midst of pain. The chapter that deals with Black rage and mostly interacts with Psalm 137 avoids the denial of reality type of escatology. But still, I am a bit ambivalent with the emphasis of hope in the title. I think the hope of the Black church in the midst of pain is part of what the white Church needs to learn. But that feels to me to be a lesson that might be several steps down the road and so I am a bit more comfortable embracing lament than hope at this point. All of that ambivalence is about my perception of white readers, not about the actual words on the page of the book.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Justin R. Garcia

Health, Mind & Body, Nonfiction (Adult), Parenting, Families, Relationships

Nicole McNichols

Health, Mind & Body, Parenting, Families, Relationships, Self-Help

Elaine N. Aron

Health, Mind & Body, Nonfiction (Adult), Self-Help