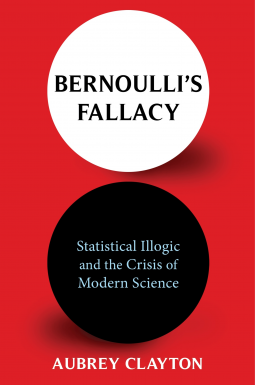

Bernoulli's Fallacy

Statistical Illogic and the Crisis of Modern Science

by Aubrey Clayton

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Aug 03 2021 | Archive Date Nov 10 2021

Talking about this book? Use #BernoullisFallacy #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

Aubrey Clayton traces the history of how statistics went astray, beginning with the groundbreaking work of the seventeenth-century mathematician Jacob Bernoulli and winding through gambling, astronomy, and genetics. Clayton recounts the feuds among rival schools of statistics, exploring the surprisingly human problems that gave rise to the discipline and the all-too-human shortcomings that derailed it. He highlights how influential nineteenth- and twentieth-century figures developed a statistical methodology they claimed was purely objective in order to silence critics of their political agendas, including eugenics.

Clayton provides a clear account of the mathematics and logic of probability, conveying complex concepts accessibly for readers interested in the statistical methods that frame our understanding of the world. He contends that we need to take a Bayesian approach—that is, to incorporate prior knowledge when reasoning with incomplete information—in order to resolve the crisis. Ranging across math, philosophy, and culture, Bernoulli’s Fallacy explains why something has gone wrong with how we use data—and how to fix it.

Advance Praise

"This story of the 'statistics wars' is gripping, and Clayton is an excellent writer. He argues that scientists have been doing statistics all wrong, a case that should have profound ramifications for medicine, biology, psychology, the social sciences, and other empirical disciplines. Few books accessible to a broad audience lay out the Bayesian case so clearly."

--Eric-Jan Wagenmakers, coauthor of Bayesian Cognitive Modeling: A Practical Course

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780231199940 |

| PRICE | $37.95 (USD) |

Average rating from 6 members

Featured Reviews

richard b, Reviewer

richard b, Reviewer

You better be wearing your big boy pants if you attempt to read this book. I took many college courses in statistics while obtaining both my Bachelor's and Master's degrees and this book was too tough even for me. (It did not help at all that the Kindle galley that I was sent did not correctly depict any of the formulas or graphs. Perhaps the final copy will correct this important shortcoming.) Mr. Clayton starts out great in Chapter One which I followed quite easily BUT then things got really tough. Unless you have a Ph.D. in statistics (I do not) this book is going to be way over your head. I suspect that for this very small group of readers that this is an excellent book but I can not be certain. Five stars for the experts who read this book and one star for the rest of us averages out to three stars overall.

Lies, Damn Lies, and Statistics. On the one hand, if this text is true, the words often attributed to Mark Twain have likely never been more true. If this text is true, you can effectively toss out any and all probaballistic claims you've ever heard. Which means virtually everything about any social science (psychology, sociology, etc). The vast bulk of climate science. Indeed, most anything that cannot be repeatedly accurately measured in verifiable ways is pretty much *gone*. On the other, the claims herein could be seen as constituting yet another battle in yet another Ivory Tower world with little real-world implications at all. Indeed, one section in particular - where the author imagines a super computer trained in the ways of the opposing camp and an unknowing statistics student - could be argued as being little more than a straight up straw man attack. And it is these very points - regarding the possibility of this being little more than an Ivory Tower battle and the seeming straw man - that form part of the reasoning for the star deduction. The other two points are these: 1) Lack of bibliography. As the text repeatedly and painfully makes the point of astounding claims requiring astounding proof, the fact that this bibliography is only about 10% of this (advance reader copy, so potentially fixable before publication) copy is quite remarkable. Particularly when considering that other science books this reader has read within the last few weeks have made far less astounding claims and yet had much lengthier bibliographies. 2) There isn't a way around this one: This is one *dense* book. I fully cop to not being able to follow *all* of the math, but the explanations seem reasonable themselves. This is simply an extremely dense book that someone that hasn't had at least Statistics 1 in college likely won't be able to follow at all, even as it not only proposes new systems of statistics but also follows the historical development of statistics and statistical thinking. And it is based, largely, on a paper that came out roughly when this reader was indeed *in* said Statistics 1 class in college - 2003. As to the actual mathematical arguments presented here and their validity, this reader will simply note that he has but a Bachelor of Science in Computer Science - and thus at least *some* knowledge of the field, but isn't anywhere near being able to confirm or refute someone possessing a PhD in some Statistics-adjacent field. But as someone who reads many books across many genres and disciplines, the overall points made in this one... well, go back to the beginning of the review. If true, they are indeed earth quaking if not shattering. But one could easily see them to just as likely be just another academic war. In the end, this is a book that is indeed recommended, though one may wish to assess their own mathematical and statistical knowledge before attempting to read this polemic.

Jeremy C, Reviewer

Jeremy C, Reviewer

I thought this book was really good. I love the Clayton didn't shy away from including equations and calculations in the book (even though I couldn't see them because of the atrocious pre-publication formatting). Clayton writes from a very specific point of view, but it's one I found persuasive. I thought this was a good explanation of a lot of the philosophical and scientific issues surrounding statistics and probability.

Pablo R, Reviewer

Pablo R, Reviewer

I'm not how to take this book or who the real audience is. The book assumes a lot more familiarity with probability theory than I have so I can't speak to the underlying theme (Bernoulli is wrong and Bayes is right). The issue is that it reads like a rant, with Clayton offering E.T. Jaynes' interpretation of Bayes as the one truth, while making blanket statements like "all challenges to the fact of systemic racism in the US justice system are wrong". It's hard to accept the message when the messenger comes across so hardnosed and doesn't follow his own advice when giving examples. I was expecting a little more historical info on the development of the field, and a balanced treatment of what's right and what's not (and why). That isn't what we have here.

Recommended for students of probability theory who want exposure to other viewpoints.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Historical Fiction, Literary Fiction, Sci Fi & Fantasy

Rachel Joyce

Historical Fiction, Literary Fiction, Women's Fiction

Brian Soonho Yoon

Children's Nonfiction, Crafts & Hobbies

Sam Morrison

Children's Nonfiction, Crafts & Hobbies, Outdoors & Nature