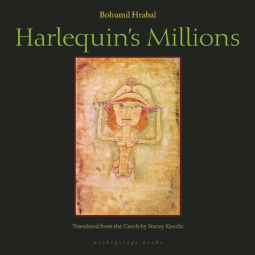

Harlequin's Millions

A Novel

by Bohumil Hrabal

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date May 06 2014 | Archive Date May 06 2014

Steerforth Press | Archipelago

Description

Praise for Too Loud a Solitude:

"Short, sharp and eccentric. Sophisticated, thought-provoking and pithy." --Spectator

"Unmissable, combines extremes of comedy and seriousness, plus pathos, slapstick, sex and violence all stirred into one delicious brew." --The Guardian

"In imaginative riches and sheer exhilaration it offers more than most books twice its size. At once tender and scatological, playful and sombre, moving and irresistibly funny." --The Independent on Sunday

Praise for I Served the King of England:

"A joyful, picaresque story, which begins with Baron Munchausen-like adventures and ends in tears and solitude." -- James Wood, The London Review of Books

"A comic novel of great inventiveness ... charming, wise, and sad--and an unexpectedly good laugh." --The Philadelphia Inquirer

"An extraordinary and subtly tragicomic novel." --The New York Times

"Dancing Lessons unfurls as a single, sometimes maddening sentence. The gambit works. Something about that slab of wordage carries the eye forward, promising an intensity simply unattainable by your regularly punctuated novel." --Ed Park, The New York Times Book Review

Advance Praise

"A surreal and loquacious tale. . . . Billed as "a fairy tale," the novel, at times, fancifully confounds expectations. . . and Hrabal's long, lyrical sentences (each chapter consists of a single paragraph) are not only eloquently constructed, but also as spirited as the scenes they illustrate." --Publishers Weekly (starred review)

"Czechoslovakia's greatest living writer." --Milan Kundera

"Hrabal, to my mind, is one of the greatest living European prose writers." --Philip Roth, 1990

"There are pages of queer magic unlike anything else currently being done with words." --The Guardian

"Hrabal is a most sophisticated novelist, with a gusting humour and hushed tenderness of detail." --Julian Barnes

"What Hrabal has created is an informal history of the indomitable Czech spirit. And perhaps ... the human spirit." --The Times

Praise for Too Loud a Solitude:

"Short, sharp and eccentric. Sophisticated, thought-provoking and pithy." --Spectator

"Unmissable, combines extremes of comedy and seriousness, plus pathos, slapstick, sex and violence all stirred into one delicious brew." --The Guardian

"In imaginative riches and sheer exhilaration it offers more than most books twice its size. At once tender and scatological, playful and sombre, moving and irresistibly funny." --The Independent on Sunday

Praise for I Served the King of England:

"A joyful, picaresque story, which begins with Baron Munchausen-like adventures and ends in tears and solitude." -- James Wood, The London Review of Books

"A comic novel of great inventiveness ... charming, wise, and sad--and an unexpectedly good laugh." --The Philadelphia Inquirer

"An extraordinary and subtly tragicomic novel." --The New York Times

"Dancing Lessons unfurls as a single, sometimes maddening sentence. The gambit works. Something about that slab of wordage carries the eye forward, promising an intensity simply unattainable by your regularly punctuated novel." --Ed Park, The New York Times Book Review

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780981955735 |

| PRICE | $18.00 (USD) |

Links

Average rating from 10 members

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Elizabeth Arnott

General Fiction (Adult), Mystery & Thrillers, Women's Fiction

Cecilia Eudave

General Fiction (Adult), Literary Fiction, Multicultural Interest