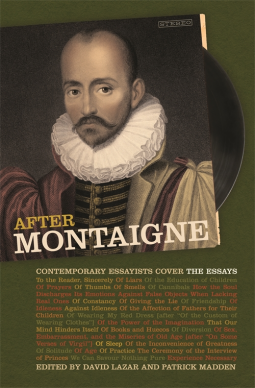

After Montaigne

Contemporary Essayists Cover the Essays

by David Lazar and Patrick Madden

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Sep 15 2015 | Archive Date Dec 16 2015

Description

Writers of the modern essay can trace their chosen genre all the way back to Michel de Montaigne (1533–92). But save for the recent notable best seller How to Live: A Life of Montaigne by Sarah Bakewell, Montaigne is largely ignored. After Montaigne—a collection of twenty-four new personal essays intended as tribute—aims to correct this collective lapse of memory and introduce modern readers and writers to their stylistic forebear.

Though it’s been over four hundred years since he began writing his essays, Montaigne’s writing is still fresh, and his use of the form as a means of self-exploration in the world around him reads as innovative—even by modern standards. He is, simply put, the writer to whom all essayists are indebted. Each contributor has chosen one of Montaigne’s 107 essays and has written his/her own essay of the same title and on the same theme, using a quote from Montaigne’s essay as an epigraph. The overall effect is akin to a covers album, with each writer offering his or her own interpretation and stylistic verve to Montaigne’s themes in ways that both reinforce and challenge the French writer’s prose, ideas, and forms. Featuring a who’s who of contemporary essayists, After Montaigne offers astartling engagement with Montaigne and the essay form while also pointing the way to the genre’s potential new directions.

Advance Praise

—Publishers Weekly

"A fascinating collection of essays that carries forward the omnidirectional momentum of the master. After Montaigne gives us grand examples of the essay as it lives today."

—Ian Frazier, author of Great Plains

“Imagine the dinner party: not just Montaigne but many Montaignes

resurrected in these brilliant essays by twenty-eight of today’s most

inventive writers. The table is crowded, enlivened by the paradoxical

warmth of Montaigne’s detachment and by the parry and thrust of ideas,

often tantamount to a kind of quiet eros. It’s a dinner full of random

appetites, the kind of party we leave knowing ourselves a little less,

which might mean a little better. What a feast this collection is. It

satisfies a hunger—intellect meeting empathy—that enlarges us.”

—Barbara Hurd, author of Listening to the Savage: River Notes and Half-Heard Melodies

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780820348155 |

| PRICE | $32.95 (USD) |

Links

Average rating from 3 members

Featured Reviews

Bill C, Reviewer

Bill C, Reviewer

Read about the essay form for more than five or six minutes, and you’re almost bound to come across a reference to Montaigne. Write essays, and it’s almost incumbent upon you to at some point confront Montaigne, who began the whole thing so long ago. Which makes it surprising it’s taken so long for an anthology that asks contemporary essayists to do just that in blunt, precise fashion, as the editors Patrick Madden and Chris Lazar relate in their introduction, comparing the essays to cover songs: “We asked more than two dozen . . . essayists to give us their take on a Montaignean subject . . . [in an] attempt to reenvision Montaigne’s topics through a contemporary sensibility.” As an added bonus, the editors also asked the authors to include a brief coda “explaining the process through which the essayist translated, transfigured, reimagined, or rethought some of the essential ideas, figures, and motifs in Montaigne’s original” (and I’d be lying if I didn’t say I preferred a few codas to the actual essays themselves). Like most collections, After Montaigne has its hits and misses, but the former easily outnumber the latter, and the scales are also tilted by the fact that the excellent essays make the worst ones mostly forgettable.

Similar to Montaigne’s originals, the essays range widely in subject and tone, range perhaps even more widely in style and structure, and finally also vary in their attitude toward their source material—some writing in concert with Montaigne, some against (some, as they tell us in the coda, began one way but ended the other), some yanking him forward in time, others content to let him remain in the past. This variety is a clear strength of the collection, as one is almost certain to find something (more than a few somethings more likely) that appeals.

I confess the collection started a bit rough for me, but hit its stride a few essays in with Lia Purpura’s standout piece “Of Prayers,” concerning the murder on one of her students by the student’s father, funneling the incident through a sharp focus on the quilt found at the crime scene: “The quilt bore the weight of the act, of the bodies; and since such fabric isn’t given to absorbing, it must have made channels, and there the blood pooled. There were runnels. And chambers.” The murder is linked as well to the suicide of one of Purpura’s close friends, an act Purpura imagines again and again, as “a new piece of that scene fills in, suggests itself, makes a bid for inclusion.” I loved the movement within this piece, the vividness of its scenes and details, the fully introspective voice, and startlement of language. This was easily my favorite piece, but far from the only strong one. My other favorites were:

Bret Lott’s “Of Giving the Lie.” I liked the way the essay was structure, along with its focus on story, use of third person, and strong sense of narrative and place.

Steven Church’s “Of Idleness” makes use of photos, historical references, and news stories as he examines his own relationship to the idea of idleness and in particular the form it takes via the teenagers that loiter in stores and public areas, but especially just across the street from his home. Throughout, one has the sense that Church is unsure himself of what he’ll learn about his attitudes, and the end scene is pitch perfect.

Barry Borich’s “Of Wearing My Red Dress” takes what could have been a breezy piece focusing on clothes and shifts quickly into a substantive, at times disturbing examination of how her social interactions and dress (the titular one in particular) intertwined.

Judith Oriz Cofer’s “Of Books and Huecos” is a poignant, moving work that begins with the author disposing of her recently deceased mother’s goods, several of which becomes vehicles for her to come to understand her immigrant mother’s two-world existence, her longing for home, and the way the author herself has “no dream of home that can compare to hers.”

In a somewhat different vein from the other essays, Chris Arthur’s “Of Solitude” is a nice overview both of Montaigne and his work and of the essay in general, bringing in his own experiences but in a less intimate fashion than many of the other writers.

Marcia Aldrich has a painful (literally and otherwise) epiphany while on a horseback ride in Mexico, made perhaps even more agonizingly effective by the reader knowing just where this piece is likely to go.

These half-dozen or so stood out particularly for me, but most others succeeded at least partially. Some I wholly enjoyed but felt they seemed not quite complete, some on the other hand went longer than I needed them to, but still had long passages that were moving or thought-provoking, and one or two didn’t compel so much in their content but were presented in an engaging voice. There were only a handful I didn’t much care for at all, and as mentioned above, these few were more than balanced by the stronger ones, making this an easy collection to recommend, whether one has read Montaigne or not.