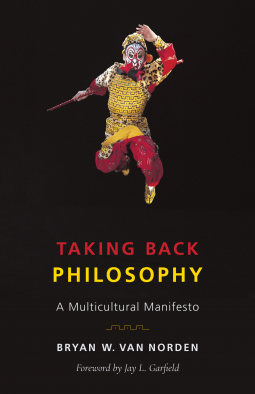

Taking Back Philosophy

A Multicultural Manifesto

by Bryan W. Van Norden

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Dec 05 2017 | Archive Date Sep 25 2018

Description

In a cheeky, agenda-setting, and controversial style, Van Norden, an expert in Chinese philosophy, proposes an inclusive, multicultural approach to philosophical inquiry. He showcases several accessible examples of how Western and Asian thinkers can be brought into productive dialogue, demonstrating that philosophy only becomes deeper as it becomes increasingly diverse and pluralistic. Taking Back Philosophy is at once a manifesto for multicultural education, an accessible introduction to Confucian and Buddhist philosophy, a critique of the ethnocentrism and anti-intellectualism characteristic of much contemporary American politics, a defense of the value of philosophy and a liberal arts education, and a call to return to the search for the good life that defined philosophy for Confucius, Socrates, and the Buddha. Building on a popular New York Times opinion piece that suggested any philosophy department that fails to teach non-Western philosophy should be renamed a “Department of European and American Philosophy,” this book will challenge any student or scholar of philosophy to reconsider what constitutes the love of wisdom.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780231184373 |

| PRICE | $27.00 (USD) |

| PAGES | 240 |

Average rating from 6 members

Featured Reviews

Reviewer 502112

Reviewer 502112

This is an excellent book of importance to current academic philosophy, because it exposes the emperor's nakedness quite definitively.

It's made up of 5 chapters, with the 1st, 2nd, and 5th being excellent and I agree with just about everything argued for there. Unfortunately, I think chapter 3 raises a serious objection that Van Norden doesn't quite address, and chapter 4 should never have been published in this volume. I deal with all of this in detail below.

I. Why this book is great

I think the book succeeds in arguing for its central thesis in Chapters 1 and 2- that as long as philosophy departments see themselves as engaged in the pursuit of universally applicable truths, the exclusion of non-Western traditions is indefensible by their own lights.

He offers three arguments for this.

1. Many texts from other intellectual traditions fall squarely within the kinds of definitions offered for "philosophy". After all, the ancient Chinese philosophers engaged in subtle argumentation and theory construction just as much as any of the ancient Greeks, so it isn't clear why only the Greeks are considered special.

2. Even if we think that philosophy as is understood today originated in ancient Greece, the kinds of questions that arose and are still discussed today are seen as important by themselves at this point. And there are many actual debates within Chinese philosophy that have direct bearing on their Western counterparts, so there's not just an abstract possibility of relevance but a real relationship that should be explored.

3. the exclusion of non-Western texts isolates and alienated those who don't come a Western background, keeping away talented non-Western kids from philosophy.

Reason #2 is especially important and Van Norden does an admirable job of pointing out real debates in contemporary Western philosophy that could benefit from input from Chinese philosophers, and gives arguments from metaphysics, political philosophy, and ethics to showcase this. He points out that Western metaphysics and political philosophy both start off by assuming the primary unit of salience is the individual, and consequently spend an inordinate amount of time on puzzles about how bigger wholes made up of discreet individuals come and stay together, with regard to both metaphysical "substances" and political communities. In contrast, Chinese philosophers start with a picture of human beings where connections to others are important aspects of who a person is. Therefore it isn't considered particularly mysterious how communities of multiple individuals adhere, since it is seen as commonsensical that there is both an individual and collective aspect of identity.

If anything Van Norden under-emphasizes how ingrained these assumptions are to Western philosophy. While its true that Hobbes theorizes about how selfish individuals come together, these basic assumptions find their way into the theorizing of modern theorists like Rawls too (who justifies it on the grounds that minimal assumptions make the theory more plausible). And then Martha Nussbaum will argue against Rawls in 'Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership' that the people "signing" the social contract don't have to be that same as those whom the social contract "protects". In an incredibly circuitous route, the assumptions of the Chinese philosophers make an appearance again.

In additions, the stance that others form a constitutive part of our selves, and that therefore we shouldn't assume atomistic individualism as basic is argued for by Michael Sandel in his 'Liberalism and the Limits of Justice', Charles Taylor is celebrated for pointing out that we need others to build our sense of self, and Mary Midgley will insist that "understanding is fitting into context".

I take these examples to support both the idea that the West can learn from Eastern traditions, and that there is massive overlap in the themes explored in multiple traditions.

On a personal note, as someone who grew up in India and studied in Singapore, although I always found Western political philosophy more interesting in its relevance to modern institutions, I always found its assumption of atomistic individualism deeply implausible regarding my own experiences. I completely see why others of similar backgrounds may turn away from such philosophizing, if they see nothing that speaks to them.

II. An unanswered objection

One place that Van Norden doesn't quite respond to an objection adequately is regarding Allan Bloom's argument from his 'The Closing of the American Mind'. According to this, it is important not just to provide young people with classics to read, but that a person first be tutored in a particular intellectual tradition for them to cultivate an identity rooted in specific particularities of their own, before they can engage meaningfully with others. Interestingly, Van Norden repeatedly points out positively that the current Chinese president Xi Jinping is trying to get China excited about Confucianism (even if it sometimes involves a superficial reading of the classic texts). Bloom might endorse Xi Jinping as participating in a philosophical project like his own, where a specific tradition is first taught, and only then students exposed to other texts.

I think this objection is important because for the most part Van Norden assumes that philosophy is right to consider itself as some general activity of the mind seeking universal truths. However, this position itself seems somewhat Cartesian, with a view-from-nowhere. If we thought that the Chinese were right that constitutive identities are important, then there really would be a need to inculcate people into a particular tradition first, and so Van Norden's call for egalitarianism of cultural texts right from the beginning for everyone might be pernicious.

Moreover, Van Norden himself seems to think that "There is more than one “great conversation” in the world, and more than one way to furnish a soul," so its not clear what his response can be to someone who argues for different parts of the world teaching their own local philosophical traditions extensively first, and only then teaching about others. I suppose, Van Norden could still argue that we would still need teachers of other traditions eventually even in this narrative, but his argument would be blunted.

This objection is particularly effective against Van Norden because he later defines philosophy as:

We are doing philosophy when we engage in dialogue about problems that are important to our culture but we don’t agree about the method for solving them...where “importance” ultimately gets its sense from the question of the way one should live.

If what is considered important varies by culture (even if with overlap), then according to this definition, what will be considered philosophy will itself vary culture by culture. So a position like Bloom's gets even more plausible.

(For my part, I think Western philosophy departments and perhaps Chinese ones have a special obligation to be diverse today because they have hoarded wealth and prestige to the point where non-Western students are forced to attend them if they want to have a real shot at a job. So sure, in an ideal world of fair distribution of wealth and influence, different philosophy departments can focus on their own local traditions, but hey, we don't live there. But note that this kind of reasoning does require ditching the self-conception of academic philosophy as engaging in a pristine and hermetic intellectual enterprise, and instead recognizing that philosophy exists amidst unfair distributions of power)

III. The parts of the book that were...meh (this is somewhat nitpicky)

Unfortunately, apart from all the really well-argued stuff, there's also a section that tries to defend philosophers from its haters. Apart from the fact that a lot of this is not new and a staple of any philosophy professor's spiel to first-year undergrads, it relies on a central equivocation.

"Philosophy" can be taken to refer to at least three distinct things:

1. Modern academic philosophy

2. The activity of the greats of the philosophical cannon that concerned themselves with thinking about how we should lead our lives.

3. The layperson's act of thinking philosophically

I think it's completely fair to think that there are links and similarities between all three, with maybe #1 and #2 being considered enhancements or systematized versions of #3. But I think all three are still distinct. However, Van Norden treats them as pretty much the same in the course of his argument.

For example, he points out that philosophy majors score very high in standardized testing and that they end up making a lot of money, which both seem very specific to #1. But he also criticizes #1 for obsessing with trivial puzzle solving instead on focusing on the big questions of importance, like how humans should live. But what if it is precisely this puzzle solving that helps students develop their minds in ways that help them score high in the LSAT? You don't have to think this is true, but its possibility shows that #1 and #2 do come apart.

In addition, there seem to be something vaguely anti-intellectual in this insistence that all philosophy needs to be concerned with fundamental questions of how we should live. As someone who thinks curiosity is a natural and fundamental impulse, I don't think philosophy needs to obsessively care about the question of how we should live in any explicit or systematic way to be considered legitimate.

(Also unrelated, in an effort to show that conservatives are paranoid, Van Norden points out that their regular predictions about how social progress will bring about the end of the world never come to pass. This is true, but this also seems somewhat unfair because there really were radical movements on the left, whose fruition would have brought about the worst of conservative predictions. So while its true for example that "Gays and lesbians...are happily integrated into [marriage]", we shouldn't forget that there was a fad in the 80s and 90s of radical queers denouncing marriage (check out Lee's Edelman's 'No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive' for a particularly out-there version of this). Similarly, today's young people are increasingly supporting socialism and getting rid of gender entirely, which even if good, are still radical. So portraying conservative concerns as being entirely rooted in delusion isn't completely fair, because the left has always had loud utopian voices seeking to upend the world. To ignore this and give a revisionist history of conservatism vs. homogeneous centrism was out of place in an otherwise nuanced book.)

IV. Coming back to why this book is great

Even with all these issues, it should be remembered that the central thesis in section I above has been ably defended, and so the book is great just because of that.

But in addition, this is also a really well-written book because it is accessible, funny, and surprising. For example, after a few pages of some deeply uncharitably readings of Western philosophers, he goes:

"My mainstream philosophical colleagues are champing at the bit to point out that I have taken these selections from Plato and Aristotle out of context. The allegory of the cave is part of a complex and subtle epistemological and ethical project. Aristotle’s poetic comment about pleasure comes at the end of a tightly argued discussion, and must be interpreted in the light of his nuanced view of properties. You’re quite right. But perhaps now you can understand my frustration with those who treat Chinese philosophy as nothing but context-less koans or fortune-cookie platitudes."

This is a hilarious way of making his point. And after a relatively dense section where he pinpoints the precise arguments and authors in Chinese philosophy with relevance to contemporary Western debates, Van Norden goes:

"However, this chapter discusses subtle and complex issues in only a few pages, so I would be surprised if you found nothing you want to challenge. In fact, if you have no questions or objections, I’m disappointed in you."

I love this, this reminds me of all the best teachers I've had- possessing the ability to challenge you with new content but also inviting you to outmaneuver them right back. He's right that philosophy is one of the few places where a "hermeneutic of faith" is still practiced, and he makes his own argument (for the most part) with charity, patience, and humour, making it an academic philosophy text which is actually both insightful and enjoyable.

At the end of it all, the emperor's clothes have been revealed to be non-existent, and the farcical nature of a discipline which claims to pursue objective and universal truth while strangely managing to ignore the vast majority of intellectual traditions becomes undeniable.

That's not to say that all the questions have been answered by Van Norden, I've even pointed out some questions above. It is also unclear how much diversity will a department need to have for fairness, and if this will vary depending of contextual factors (probably). But I for one also look forward to the new comparative studies that will inevitably rise when different traditions are allowed to meet. For example, Franklin Perkins' fascinating paper, 'The Greatest Mistake', argues that one reason modern Science didn't take off in China was the coherent and reasonable metaphysics employed there, unlike the then unwarranted claims to the possibility of knowledge made by Christian Europeans. This is a (possible) pattern invisible without alternative traditions to learn from and contrast, and who knows how many more patterns are out there, waiting to be discovered. To paraphrase John Stuart Mill, “he who knows only his own philosophical tradition knows little of that."

Originally posted: https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/2413872101

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Nik Xandir Wolf

General Fiction (Adult), Mystery & Thrillers, Novellas & Short Stories

We Are Bookish

Mystery & Thrillers, OwnVoices, Teens & YA

L.M Montgomery

Children's Fiction, Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, Teens & YA

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, Mystery & Thrillers, Teens & YA