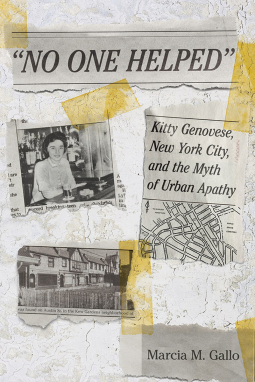

"No One Helped"

Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy

by Marcia M. Gallo

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Aug 11 2015 | Archive Date Apr 14 2015

Description

In "No One Helped" Marcia M. Gallo examines one of America's most infamous true-crime stories: the 1964 rape and murder of Catherine "Kitty" Genovese in a middle-class neighborhood of Queens, New York. Front-page reports in the New York Times incorrectly identified thirty-eight indifferent witnesses to the crime, fueling fears of apathy and urban decay. Genovese's life, including her lesbian relationship, also was obscured in media accounts of the crime. Fifty years later, the story of Kitty Genovese continues to circulate in popular culture. Although it is now widely known that there were far fewer actual witnesses to the crime than was reported in 1964, the moral of the story continues to be urban apathy. "No One Helped" traces the Genovese story's development and resilience while challenging the myth it created."No One Helped" places the conscious creation and promotion of the Genovese story within a changing urban environment. Gallo reviews New York's shifting racial and economic demographics and explores post–World War II examinations of conscience regarding the horrors of Nazism. These were important factors in the uncritical acceptance of the story by most media, political leaders, and the public despite repeated protests from Genovese's Kew Gardens neighbors at their inaccurate portrayal. The crime led to advances in criminal justice and psychology, such as the development of the 911 emergency system and numerous studies of bystander behaviors. Gallo emphasizes that the response to the crime also led to increased community organizing as well as feminist campaigns against sexual violence. Even though the particulars of the sad story of her death were distorted, Kitty Genovese left an enduring legacy of positive changes to the urban environment.

Advance Praise

"In 'No One Helped,' Marcia M. Gallo

tells you why everything you’ve heard about Kitty Genovese and her death

is wrong, how this came to be, and why it matters. In this valuable

book, which sheds light on crime, the media, and New York City, we meet

Genovese not as a victim but as a fierce and fascinating woman whose

story can inspire people to live boldly and help people in

peril."—Robert W. Snyder, Rutgers University, Newark, author of Crossing Broadway: Washington Heights and the Promise of New York City

"'No One Helped' is a provocative, timely, and important book.

Marcia M. Gallo has fully conceptualized and explained the textures of

the various communities involved in the Kitty Genovese story: the city

of New York, the borough of Queens, the neighborhood of Kew Gardens, the

bar where Genovese worked, and the nascent lesbian and gay community,

among others. This is a remarkable story, and Gallo does fine work

making visible the substance of the lives of the main players in this

saga."—Leisa Meyer, Class of 1964 Distinguished Associate Professor of

American Studies and History, College of William & Mary, author of Creating G.I. Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II

"Marcia M. Gallo's historically narrative approach to the Kitty

Genovese murder is clear and accessible. Gallo's admirably balanced

treatment draws on media coverage, oral history, social scientific

literature, and changing memories of the crime."—Karen Halttunen,

University of Southern California, author of Murder Most Foul: The Killer and the American Gothic Imagination

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9780801456640 |

| PRICE | $24.95 (USD) |

Links

Average rating from 29 members

Featured Reviews

Lectus R, Librarian

Lectus R, Librarian

Very well researched. The book is also a history of how Queens have become the diverse borough it is today.

Pictues and newspaper clippings support the book throughout.

I live in Queens and had heard of that crime. It was interesting reading how we, New Yorkers, let crimes to be committed because "we don't want to get involved."

People in New York, as a whole, display a high degree of apathy. I think it has been decreasing since 9/11, though.

Anne M, Reviewer

Anne M, Reviewer

REVIEW of “NO ONE HELPED” by Marcia M Gallo

This book should be compulsory reading for every student of psychology, social psychology and journalism. The good news is that it is a well-written and easy to read narrative.

Existing students will be aware of the Kitty Genovese murder in New York in 1964. It led to research and the development of “the Bystander Effect” which states that it is better to be attacked or come to harm in front of a few than in front of many as when there are many, no one acts. The tragic murder of the young woman in the early hours of the morning produced many column inches and several books. The myth of her murder as reported (especially in the New York Times) was that 38 of her neighbours “witnessed” her murder and did nothing, that they ignored her screams despite her being attacked 3 times and that the apathy of her fairly well to do area led to her death because no one called the police. These “facts” have been picked up in textbooks for years and are rarely corrected.

This is where Ms Gallo takes up the story in light of the 50th anniversary of the horrendous crime. And Ms Gallo tells a totally different story – as do many others including the editor of the New York Times at the time who has somewhat recanted from his position that “38 witnesses did nothing”.

The truth of the circumstances of Kitty Genovese’s horrible death is that she was stabbed outside the building where she lived and her screams were heard and acted upon. Several people phoned the police but her attacker followed her into the lobby of her apartment and stabbed her in the throat to stop her screams. A neighbour who was a nurse came to her aid and held her until the police and ambulance came but Kitty died on the way to the hospital. So she was stabbed twice, people did phone the police, someone came to her aid and most of the 38 (or 37 or 39) people who lived in the block heard nothing, as it was 3:30 in the morning. Hardly witnesses. But the real story isn’t as exciting as the one created by the media.

Also interesting was how Ms Genovese became a cypher and stopped being “herself” or being “real”. She was a lesbian living with her girlfriend who is still also haunted by the thought that maybe she could have “done something” that fateful night, despite the fact that no one could have saved Kitty. Her murderer (subsequently caught and found to have murdered previously who then escaped and attacked again) was intent on killing her.

Also there was no easy method of phoning the police at the time. By 1937 the 999 service was in use throughout England. Australia and New Zealand introduced it the following year and Winnipeg in North America adopted it in 1959. But in New York there was confusion about how to call police. For example Gallo shows that the telephone for Staten Island police is SAint George 7-1200 yet the police department official roster at the time showed it as ST George 7-1200. When NY did introduce a single number after the Genovese murder it was 440-1234 which as many commented isn’t easy to call when panicked or in the dark.

The book goes through the social and cultural changes in New York at the time and over the subsequent years showing the opposite of apathy. There were huge movements for change and at times concerns about tipping into vigilantism – Curtis Sliwa started the Guardian Angels in 1979 and Bernard Goetz (the Subway vigilante) pulled a gun on people trying to rob him on a train and shot one of them.

More recent psychologists noted that –

“Thus the three key features of the Kitty Genovese story that appear in social psychology textbooks (that there were 38 witnesses, that the witnesses watched from their windows for the duration of the attack and that the witnesses did not intervene) are not supported by the available evidence.”

Ms Gallo has done the memory of Kitty Genovese a great service as well as the many activists at the time – the New York Times editor who was largely responsible for the inaccuracies in the murder reporting was heard to ask at an editorial meeting “Where did all these…. these queers come from” and this led to a front-page story on how “Problem of Homosexuality in City Provokes Wide Spread Concern” in December 1963 shortly before Ms Genovese’s death in 1964.

The city of New York had many residents who were organizing and getting involved, defying the myth of urban apathy.

This book is clearly written, easy to read and the footnotes are kept separate allowing further study if required without interrupting the flow. It raises many questions about motives and methods within journalism and politics and is a sobering read. Ms Genovese deserves no less.

Collette M, Reviewer

Collette M, Reviewer

An extremely well researched book was not one I would normally read I found it fascinating and informative. The crime the book deals with was one I had not heard of before but the resulting changes to so many elements in society are amazing when explained as they are by the author.

From an early age, I longed for the big city life. Growing up in a sleepy township that didn’t even have sidewalks will do thatNo One Helped to a kid. To dissuade me from fleeing the Rust Belt for bright lights and tall buildings, my parents served up the tale of Kitty Genovese, the New York woman who, in 1964, was famously murdered on a Long Island street while everyone just stood back and watched her die.

It terrified me. In my mind, I envisioned a crowded street, broad daylight, pedestrians having to sidestep this dying stranger as she pleaded with them for help.

It wasn’t difficult to imagine. Though not the best time for New York City, the 1970s and early ’80s was a fruitful period for dystopian cinema set in the metropolis. My impression of the city was shaped entirely by Escape from New York and Fort Apache, the Bronx.

Though the story of a woman left to die on the sidewalk stayed with me, I never actually learned her name until college, when we studied the case in psychology class. Many psychology classes, actually. At the time, the prevailing narrative was still treated as gospel: 38 neighbors watched and did nothing as Winston Moseley assaulted Genovese, left, assaulted her a second time, left, and came back a third time to finish the job.

It’s hard to fathom how this could happen, and of course, it didn’t. At least, not the way it was reported in 1964, and certainly not the way it had been mythologized by the time it reached my ears as a cautionary tale. A more accurate telling was done by Kevin Cook in 2014’s Kitty Genovese: The Murder, the Bystanders, the Crime that Changed America.

The focus of Marcia M. Gallo’s “No One Helped”: Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy is not so much on the murder as the social incubator in which the narrative of urban apathy was spawned and evolved — and how, by focusing on the witnesses rather than the victim or perpetrator, Genovese “had been flattened out, whitewashed, re-created as an ideal victim in service to the construction of a powerful parable of apathy.”

The biggest omission from Genovese’s story, writes Gallo, a history professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, is that she was a lesbian. Being young, pretty and white made her the perfect media martyr, so details of her romantic preference would have been inconvenient to the “ideal victim” narrative in 1964. As the story of her murder took on a life of its own, she became a nameless victim of urban decay — more of a plot device than a character in her own horror show.

“No One Helped” is on the shorter side, but Gallo deftly packs in a lot of information — and unpacks five decades of history. The chapters are like linked short stories, exploring in turn the history of Kew Gardens and the racial tensions of the time, the changing media landscape and the marketability of an erroneous New York Times article that fumbled the facts but resonated with “white flight” suburbanites.

As for Genovese, Gallo writes, the article “rhetorically reduced her to the chalk outline left on the sidewalk at a crime scene after a body has been removed.”

About those 38 witnesses? Only four were actually called to testify at the trial, and even fewer were aware that Genovese had been stabbed. The Times failed to mention the fact that Moseley’s initial assault was interrupted by a neighbor’s intervention, and his second assault took place in a darkened back hallway beyond the vantage point of any neighbors.

Gallo writes, “In all of the accounts that have followed in the story’s wake, what has rarely been noted is that there is only one actual eyewitness to Genovese’s death. That person is her killer, Winston Moseley.”

In reclaiming Genovese’s identity, Gallo reveals her personal connection to the case. She does so in a tasteful, informative manner, steering clear of navel gazing and drawing attention instead to the resonating significance of the story.

For all the horror of the Genovese murder, and its aftermath, it also gave birth to the 911 emergency response system and community policing efforts. It furthered the movement to reexamine our societal acceptance of intimate partner violence (some witnesses had dismissed the assault as a “lover’s quarrel”).

And it exposed racial bias in crime reporting. Just two weeks earlier, Moseley had assaulted another woman, murdered her and set her on fire. “Significantly, no photographs of Moseley’s earlier victim, Anna Mae Johnson, a young black woman, ever appeared. Within weeks she would fade from most popular versions of the story, as would her killer,” the author writes.

Most of all, for Gallo, the legacy of the Genovese murder still matters “because it raises the central question of how we engage with those around us, individually and collectively, when they need our help.”

Digging beyond the murder and the myth, Gallo has penned a remarkable portrait of Genovese and her enduring legacy a half-century later. Her murder inspired an entire branch of psychology, but perhaps her lasting impact on social science will be the study of media myth-making. No matter the fables and fallacies that have emerged, the impact of Genovese has endured.

I’ve been on the Long Island Railroad, and at the Kew Gardens stop, it’s impossible not to look down at the nondescript parking lot and the neighboring houses, all crammed together, and wonder how this could have happened.

After 50 years, we know it happened differently than we’ve believed, but the true story of the assault is still as brutal and horrifying, if different, than we imagined. Gallo succeeds in redirecting our attention from the “witnesses” to the victim, who became a footnote to the fable. “No One Helped” restores the individual who existed before the chalk outline.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Sheinelle Jones

Biographies & Memoirs, Parenting, Families, Relationships, Self-Help

Jakub Politzer (Illustrator), Christina Dumalasova (adapter), Katerina Horakova (adapter)

Comics, Graphic Novels, Manga, General Fiction (Adult)