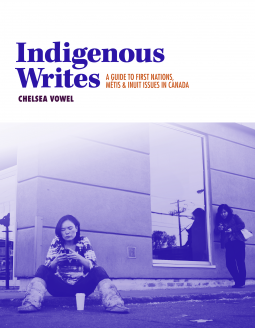

Indigenous Writes

A Guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit issues in Canada

by Chelsea Vowel

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date Sep 09 2016 | Archive Date Sep 09 2016

Portage & Main Press | HighWater Press

Description

Advance Praise

--Audra Simpson , Author of Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Columbia University

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9781553796800 |

| PRICE | $29.00 (USD) |

Links

Average rating from 2 members

Featured Reviews

Librarian 17772

Librarian 17772

Well, I'll be buying this one for the library. It becomes clear early on that Vowel wants to bring some realities home to Canadians when she follows a chapter on what the polite, current terms for referring to Indigenous people are with a chapter on what to call everyone in Canada who isn't Indigenous. This isn't just a polite recitation of things non-Indigenous people should know about their Indigenous neighbours, it's going to say a few things about its (presumably non-Indigenous) readers, too.

Fortunately, though Vowel's clearly not interested in taking any crap, she writes in a breezy, approachable style that should appeal to a broad audience, even while throwing in enough footnotes to keep the more academically inclined happy.

Many times I found a question popping into my head, only for Vowel to address it a page or two later. She's fully engaged with pop culture, referring one minute to science fiction novelist Robert J. Sawyer (not Indigenous), the next to musicians A Tribe Called Red. The book feels current. (Yes, the Daniels decision from April 2016 is in here.) And if it sounds like it might be lightweight for talking about pop culture, don't worry -- you're going to get Delgamuukw, residential schools, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, and more. Shame the repeal of Section 67 from the Canadian Human Rights Act isn't in there, but I guess you can't have everything.

So, yeah, I'm buying this for the library, and maybe a print copy for me, and I'm going to recommend it to people. And not just at work.

Sometimes you see a book and you just know that it’s the book you’ve been waiting for. That was my reaction when Chelsea Vowel, who blogs and tweets as âpihtawikosisân, announced Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Issues in Canada. You really should read her blog and follow her, because she her writing is clear and informative, and she is excellent at providing further resources. This continues in her book. I was extremely excited to get my hands on a copy, because it seemed like exactly what I wanted: a series of connected but self-contained essays that explain and highlight some of the diverse issues that Indigenous peoples face in Canada. I wanted a way to continue educating myself as well as a potential classroom resource, and lndigenous Writes lives up in every respect.

Indigenous Writes is an attempt to start these conversations in an honest, heartfelt way that is rigorous in its resources and research yet also accessible rather than academic. Vowel doesn’t assume any prior knowledge; she starts right off with a few chapters on terminology, like the differences between Indigenous, Aboriginal, Indian, First Nations, etc. From there, each essay addresses one of the numerous questions, concerns, or myths that tend to crop up over and over about Indigenous peoples, including: what “status” is and who gets it; what defines whether someone belongs to an Indigenous people, as well as more specifically what makes someone Métis; the fact that we tend to be uncomfortable, as a society, with Indigenous practices spilling over into what we perceive as “non-Indigenous” spaces, and how that becomes a transgression; as well as myths about taxes, progress, alcoholism, authenticity, etc. I wish I could just list all 31 chapter titles here! I cracked the book open to the table of contents when I first received it, and I just smiled at how much stuff Vowel manages to talk about. This is not a thick book, and the chapters themselves are seldom very long, but it is still so broadly informative.

Why do we need this book? Vowel herself eloquently provides the reason. Speaking about how settlers often deride Indigenous people from rural areas for not being familiar with urban life, she says:

> On the other side, there is no expectation within Canadian (non-Indigenous) culture that Indigenous cultures must be accounted for, learned about, or even really accommodated. Knowing nothing about the Inuit, for example, is not considered a fault. Yet when Nunavummiut (Inuit of Nunavut) or Nunavimmiut (Inuit of Nunavik) go south, their lack of knowledge about city culture/living is considered to stem from small-mindedness, a lack of education, or ignorance.

Part of having (in my case) white privilege is being able to ignore not just the problems that Indigenous peoples face but, you know, their actual existence and culture entirely. Yet we expect—no, demand—that Indigenous people are familiar with settler culture, customs, and laws. That’s a little thing called colonialism, son, and it isn’t over just because we broke away from Britain.

I see this expectation manifest almost every day. I teach adults who come from remote communities in Northern Ontario to Thunder Bay on the invitation of Matawa First Nations in order to take the classes they need to finish their high school diploma and then get training for the workforce. Very often my students come from reserves with poor access to clean drinking water, poor housing conditions, little or no Internet and cell phone access, etc. Yet we expect them to somehow adjust to relocating to a city, often with young children in tow, and get used to attending classes all day for months at a time. And this is a group of students who have the support of each other, as well as Indigenous social workers, elders, etc. If they find it tough, imagine how daunting it can be for someone who does this on their own.

When the most recent (I hate having to write that, hate that there has been more than one) news cycle about the suicide crisis in Attawapiskat erupted, letters to the editor in The Chronicle Journal suggested “closing” these northern communities and relocating their inhabitants closer to urban centres like Thunder Bay. (Insert Picard facepalm here.) Aside from the incredible tone-deafness and irony of the idea that settlers should be relocating Indigenous peoples because we’ve decided what’s best for them, I was just so amazed by the lack of empathy coming from the people who had written those letters. They acted as if the people and the culture are the problem, rather than the fact we still tacitly expect assimilation even if we claim otherwise. I’m a mellow person, and I was getting angry about it—and again, I’m a settler and have all the privileges that entails, so I can’t even begin to imagine how people more connected and involved with these issues are feeling. It’s unconscionable, the state of things, yet we let it go on.

Clearly, education is an important and pressing matter, both in terms of educating wider Canadian society about Indigenous peoples and making sure that Indigenous people receive the education they need to succeed. The big buzzword these days is reconciliation. That’s a big word for me to define comprehensively, but I think part of reconciliation must entail better knowledge of Indigenous cultures and history. Yet Vowel points out in her chapter on residential schools that most provinces’ curricula do not live up to promises to teach more thoroughly about these things. When these subjects come up, they tend to be discussed in the past tense, locating the problems and the people in history.

The wider problem that Vowel also touches on in the final chapter of Indigenous Writes is that schooling in Canada is still very Westernized and therefore assimilationist. I get what she means. Although I am proud that my job involves helping Indigenous adults get their high school diplomas, I also often reflect on the extent to which I am complicit in perpetuating colonial curriculum and approaches to education. I do what I can to bring Indigenous content into the classroom: we talk about the treaties, about systemic discrimination, about residential schools. I try to listen to my students and get help from my Indigenous colleagues. At the end of the day, though, I am still evaluating these students against expectations grounded more in Western ideas of industrialized, rationalist education than anything else. That bothers me, a lot.

Indigenous Writes is going to make an excellent resource for classroom teachers like myself. It will help us educate ourselves so we can understand these issues better, and we can even use some of these essays, or the resources that Vowel references, in our classes. But I don’t think that goes far enough. We really need to change the entire system of education. Or, as Vowel puts it at the end of this chapter:

> Indigenous communities as a whole simply do not have the internal resources to create an entire system of private schooling to rectify the horrendous gap that has always existed between Indigenous and non-Indigenous student outcomes. If you can judge a society by its system of education, then Canada stands clearly guilty of discriminating against Indigenous peoples by allowing this situation to continue.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this is the last chapter, and because there is no afterword or epilogue, this is Vowel’s closing statement for the entire book. It is a challenge to the idea that Canada does not discriminate, and a challenge to us to do something to make the system better.

I know what you’re thinking, though: OK, Ben, so you love this book as a teacher, but I’m not a teacher, so what would I get out of it? I’m glad you asked, invisible straw person voice.

It comes down to this, really: I keep having to remind myself is that the Canada I see—the Canada I grew up believing in—is not the Canada that many Indigenous people see. Growing up in a reserve, or growing up in a city but being exposed constantly to racist remarks or the threat of violence or being treated with suspicion and stereotyping … that necessarily brings about a different perspective. That’s what Vowel is trying to show us with Indigenous Writes. We Canadians pride ourselves on diversity and multiculturalism, yet some of us then turn around and leave racist comments on articles about missing and murdered Indigenous women, or we talk about how Indigenous people already have it too good in this country. It is a cognitive dissonance that is tragic, because it is quite literally killing people. If our country is as good and strong as we like to claim it is, we should be able to have a conversation about racism and actually act to end it.

It’s very easy to homogenize and lump all Indigenous peoples together when discussing “Indigenous issues”, and Vowel very deftly avoids generalizations. She discusses issues that tend to be common across the land, such as land claims, access to drinking water, stereotypes and myths and racism; she also discusses issues specific to the Inuit, Métis, and even particular nations. When she does this, lets her sense of humour come through, occasionally unleashing some well-deserved sarcasm as she dismantles an argument she has clearly dealt with too many times before. Like me, Vowel loves science fiction, and I greatly enjoyed how she references, analyzes, and deconstructs some authors’ portrayals of Indigenous peoples in their writing. Indigenous Writes is basically the rigour you’d expect from an academic textbook (the amount of endnotes alone could maim you if you dropped them on your toes) without the typically dry writing. It is the best of both world, academic and activist.

This is not always an easy book to read. There were times I had to take a break. Reading the essays back to back, it can feel very overwhelming, all of it, and unlike Indigenous people, I haven’t even lived it. Vowel recognizes the potential for succumbing to hopelessness, and she is quick to point out alternatives. She points to the staggering amount of research already presented on how to start the process of reconciliation: there’s the Neegan Burnside report on how to fix the urgent issue of drinking water on reserves; there is the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples with its complex, comprehensive twenty-year plan that fell by the wayside; there is, of course, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report on the legacy of residential schools. There are indeed thorny issues here, but we have the ingredients for beginning to solve them. We just need to actually, you know, acknowledge the problem and start doing something about it instead of locating the problems in the past or twiddling our thumbs and agreeing that it’s awful but, hey, what can you do? We need to stop blaming Indigenous people for existing, for still being here after centuries of us trying to wipe them out, and stop blaming them or their cultures for the problems that currently beset their communities.

You or I, on our own, of course cannot end or undo centuries of colonization, discrimination, and assimilation. But we can start, as individuals, by filling the gaps in our knowledge, challenging our own internalized racism, and checking our privilege. We need to have conversations about this—but remember that any given Indigenous person is under no obligation to educate settlers about these issues: that is on us! So when someone like Chelsea Vowel deigns not just to speak up, but to provide us with an invaluable, detailed collection of essays and endnotes, we need to pay attention.

What is an "American Indian"? Seems like an easy enough question. And I am sure we all have an idea in our mind.

And we are probably all wrong.

This book. This book should be read by everyone. It should be read by Canadians. It should be read by Americans. The rest of the world can read it too, if they want. The point is, this book breaks down and explains to the "settlers", to the children of colonialists, to the non-indigenous what Indigenous peoples are. And as Chelsea says:

<blockquote>The Canadian government basically takes the position that "you're an Indian if we say you're an Indian"</blockquote>

You would think that you might not need a whole book about First Nation people. How could Chelsea have that much to say, but she does, and there is that much. Because we aren't educated in Indigenous history. If we are taught about Indians at all, at least in American schools, it is as a part of history, as though they were all removed from modern times. As one Native American told me, it makes him feel invisible, as though he is not standing there.

Chelsea has a wry sense of humor and although she is educating, she is also entertaining. Her main sections are Terminology of Relationship (about who are Indians), Culture and Identity (what it says on the tin), Myth Busting (all the things you thought you knew about Indians, such as that they got free housing, that they are more susceptible to being drunk and that they don't have to pay taxes, to name a few), State Violence (where she discusses Residency School, and forced fostering out of Native children to non Native families), and Land, Learning, Law and Treaties.

And if you are this point, rolling your eyes, and saying, oh, that sounds boring, it isn't.

The author likes to pull out interesting facts such as:

<blockquote>...from 1941 to 1978, Inuit were forced to weare"Eskimo" identification discs similar to dog tags. This was for ease of colonial administration, as the bureaucrats had difficulty pronousing Inuit names, and the Inuit, at this time, did not have surnames. For a while, Inuit were officially defined as "one to whom an identification disc has been issued.</blockquote>

She also has some comments on how Indians are defined by their blood.

<blockquote>The idea that Indian blood has some sort of magic quality that imbues one with legitimate Indigenous culture is as ridiculous a notion as I can think of, and so is the idea that "outside" blood can dilute or destroy Indigenous culture.</blockqutoe>

This is such an important book. I do hope that others read it, and perhaps get some idea of what the Indigenous peoples have gone through. There has been and still is so much prejudice against them, and such unfairness. It is important that they speak out, are published, and well read. We could all stand to have a little education.

Thanks to Netgalley, and Highwater Press for making this book available for an honest review.